Paper Monuments combines public education and collaborative design to expand our collective understanding of New Orleans.

Black Women in Public Housing: A Movement Without Marches

Artist: CeCe Givens

Storyteller: Shana M. griffin

Starting in the 1920s and rising exponentially in the 1930s, the urban landscape of New Orleans, like many municipalities across the country, began to change as a result of a series of racially restrictive covenants and zoning ordinances, New Deal housing policies, blight and slum clearance initiatives, and mortgage lending practices—all informed by Jim and Jane Crow racial ideologies. These changes took root with the passage of several federal and state acts, key among them was the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Act of 1933, the National Housing Act of 1934 that established the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), and the Housing Act of 1937, also known as the Wagner-Steagall Bill, which created the United States Housing Authority.

The formation of the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) to refinanced mortgages in default to prevent foreclosures, and HOLC’s subsequent color-coded Residential Security Maps, or what is commonly referred to as redlining maps, to measure real estate risk assessment of neighborhoods based on its racial composition. set up a discriminatory practice of urban divestment and exclusion. Outlined in the lending protocols of the FHA’s Underwriting Handbook, redlining institutionalized racial residential segregation, discrimination in mortgage lending, wealth inequality, and urban divestment.

The establishment of the Housing Authority of New Orleans (HANO) by the Louisiana Housing Act of 1936, coupled with the passage of the federal Housing Act of 1937, charged with coordinating and financing the construction of public housing developments in urban settings, set the stage for the displacement and relocation of low-income Black residents into public housing.

--

In 1938 New Orleans became the first city in the country to receive federal funding under the Housing Act of 1937, codifying residential segregation in public housing and stifling the social positioning of black residents. This had a particular impact on low-income black women residents of public housing, who were routinely demonized publicly because of who they were, where they lived, how much they made, and the composition of their families; and targeted by criminalizing policies that justified their mistreatment. For decades, nearly all mortgages underwritten by the FHA supported white families, while private banks and financing institutions using FHA guidelines discriminated against black households seeking mortgage assistance in the neighborhoods in which they resided and those they attempted to relocate to. Slum clearance and urban renewal projects disproportionally uprooted black communities. Locations chosen for public housing developments both displaced and confined black people to racially and economically segregated neighborhoods, often re-housing residents in the very same public housing developments that initially displaced them.

Within its first three years, HANO secured $30 million in federal loan contracts for the construction of public housing. By the time the U.S. entered World War II in 1942, the first six public housing developments in the city were completely occupied. Four developments were reserved for Black families—the Magnolia (1941) Lafitte (1941), Calliope (1942), St. Bernard (1942), while white families occupied the St. Thomas (1941) and Iberville (1941) housing projects.

By 1957, HANO was the fourth largest public housing authority in the country managing over 10,000 units or public housing with Desire (1956) being the largest and most isolated from the rest of the city. Low-income black women found it difficult to find places to live in this continually changing housing landscape as racial and gender stereotypes, biases, and fears combined in insidious ways rendering public housing, for many, their only ‘choice.’ Public housing became sites of housing security, contradictions, activism, demonization, violence, community, poverty, and isolation.

--

Hidden within the history of public and subsidized housing in New Orleans are narratives of black women who engaged in decades-long advocacy and organizing practices that stood on the margins of traditional Civil Rights and social justice activism. Theirs was a movement without marches.

Circumscribed by opportunity and inequality, possibilities and restrictions, affordability and surveillance, low-income black woman organized to improve the lives of public housing residents, transform housing policies, advance tenant rights, encourage resident engagement, support policy changes, and participate in community building efforts through partnerships and collaborations.

With the formal incorporation of The New Orleans Public Housing Tenants, Inc. in 1972, and the establishment of the Community Services Department at HANO in 1974, public housing residents significantly increased their involvement in shaping management decision-making affecting their lives and communities.

Unable to actualize many rights gained during the Civil Rights Movement, low-income black women in New Orleans, like many of their counterparts in urban cities across the country, developed mechanisms to address the harsh circumstances of the everyday violence of racist and sexist housing policies and the irresponsibility of government actions and inactions that accompanied living in ‘the projects.’

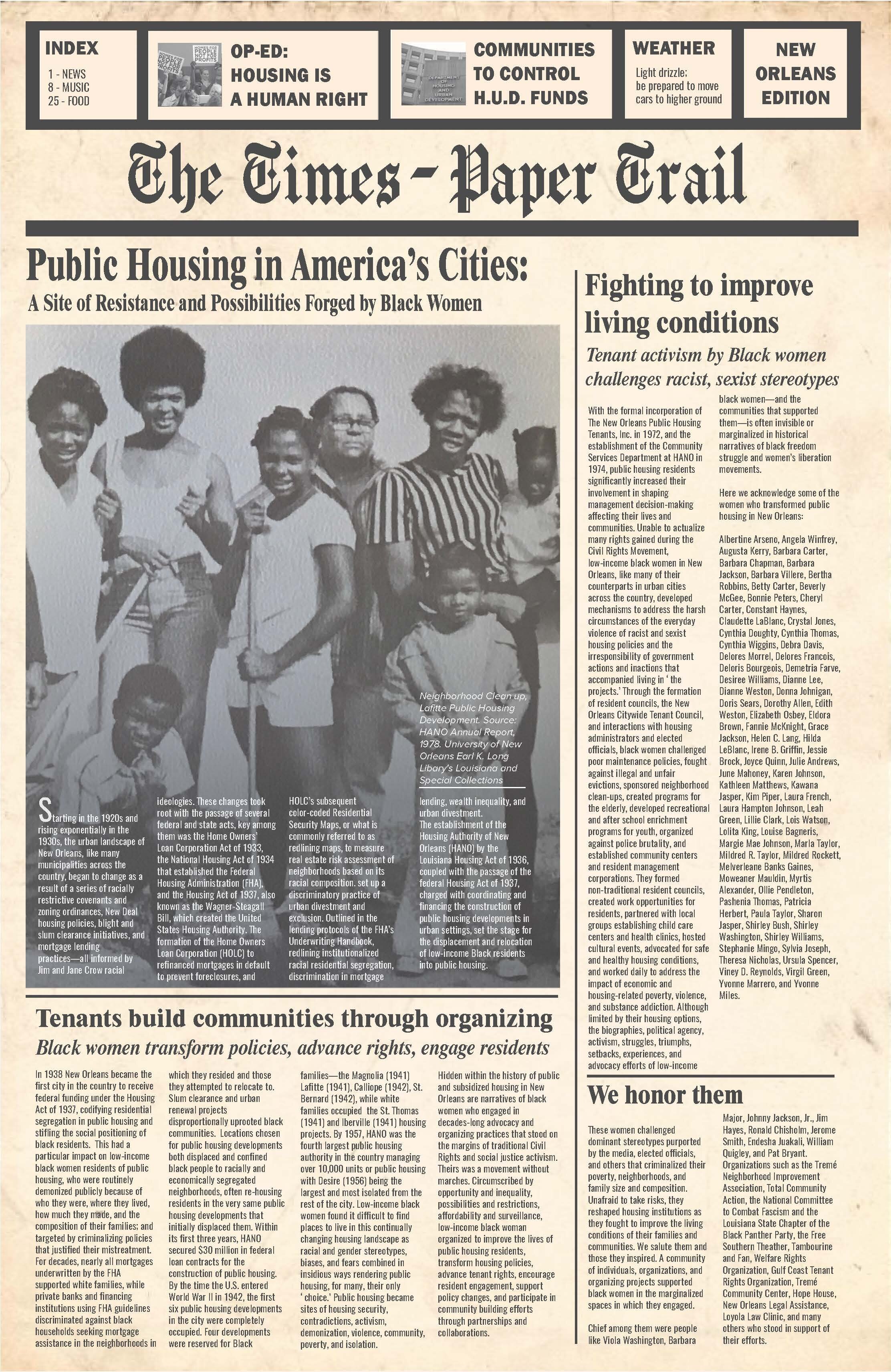

Through the formation of resident councils, the New Orleans Citywide Tenant Council, and interactions with housing administrators and elected officials, black women challenged poor maintenance policies, fought against illegal and unfair evictions, sponsored neighborhood clean-ups, created programs for the elderly, developed recreational and after school enrichment programs for youth, organized against police brutality, and established community centers and resident management corporations. They formed non-traditional resident councils, created work opportunities for residents, partnered with local groups establishing child care centers and health clinics, hosted cultural events, advocated for safe and healthy housing conditions, and worked daily to address the impact of economic and housing-related poverty, violence, and substance addiction.

Although limited by their housing options, the biographies, political agency, activism, struggles, triumphs, setbacks, experiences, and advocacy efforts of low-income black women—and the communities that supported them—is often invisible or marginalized in historical narratives of black freedom struggle and women’s liberation movements.

Here we acknowledge some of the women who transformed public housing in New Orleans:

Albertine Arseno, Angela Winfrey, Augusta Kerry, Barbara Carter, Barbara Chapman, Barbara Jackson, Barbara Villere, Bertha Robbins, Betty Carter, Beverly McGee, Bonnie Peters, Cheryl Carter, Constant Haynes, Claudette LaBlanc, Crystal Jones, Cynthia Doughty, Cynthia Thomas, Cynthia Wiggins, Debra Davis, Delores Morrel, Delores Francois, Deloris Bourgeois, Demetria Farve, Desiree Williams, Dianne Lee, Dianne Weston, Donna Johnigan, Doris Sears, Dorothy Allen, Edith Weston, Elizabeth Osbey, Eldora Brown, Fannie McKnight, Grace Jackson, Helen C. Lang, Hilda LeBlanc, Irene B. Griffin, Jessie Brock, Joyce Quinn, Julie Andrews, June Mahoney, Karen Johnson, Kathleen Matthews, Kawana Jasper, Kim Piper, Laura French, Laura Hampton Johnson, Leah Green, Lillie Clark, Lois Watson, Lolita King, Louise Bagneris, Margie Mae Johnson, Marla Taylor, Mildred R. Taylor, Mildred Rockett, Melverleane Banks Gaines, Moweaner Mauldin, Myrtis Alexander, Ollie Pendleton, Pashenia Thomas, Patricia Herbert, Paula Taylor, Sharon Jasper, Shirley Bush, Shirley Washington, Shirley Williams, Stephanie Mingo, Sylvia Joseph, Theresa Nicholas, Ursula Spencer, Viney D. Reynolds, Virgil Green, Yvonne Marrero, and Yvonne Miles.

These women challenged dominant stereotypes purported by the media, elected officials, and others that criminalized their poverty, neighborhoods, and family size and composition. Unafraid to take risks, they reshaped housing institutions as they fought to improve the living conditions of their families and communities. We salute them and those they inspired.

--

*A community of individuals, organizations, and organizing projects supported black women in the marginalized spaces in which they engaged. Chief among them were people like Viola Washington, Barbara Major, Johnny Jackson, Jr., Jim Hayes, Ronald Chisholm, Jerome Smith, Endesha Juakali, William Quigley, and Pat Bryant. Organizations such as the Tremé Neighborhood Improvement Association, Total Community Action, the National Committee to Combat Fascism and the Louisiana State Chapter of the Black Panther Party, the Free Southern Theather, Tambourine and Fan, Welfare Rights Organization, Gulf Coast Tenant Rights Organization, Tremé Community Center, Hope House, New Orleans Legal Assistance, Loyola Law Clinic, and many others who stood in support of their efforts.